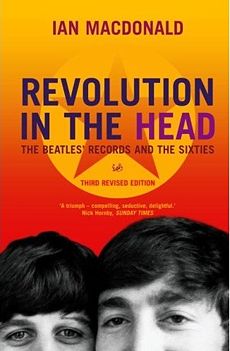

Revolution in the Head

From Beatles Wiki - Interviews, Music, Beatles Quotes

Synopsis

This book hit the mid-1990s pop-cultural scene like a bolt from the blue. Well over a quarter of a century since they was Fab, it might have seemed that everything worth saying about the Beatles had already been said, several times. At that stage, the suggestion that someone could produce a genuinely fresh perspective on this most catergorised, analysed, and anthologised of pop groups seemed only marginally less unlikely than the idea that a new band might emerge from the pop field whose music could hold a candle to the imperviously incomparable legacy of the world's best-loved Liverpudlians.

But MacDonald's words leap off the page with a freshness and sense of excitment reminiscent of, say, the opening seconds of 'I Want to Hold Your Hand'. A chronological song-by-song analysis of the Beatles' output, 'Revolution in the Head' manages to make that rarest of leaps: to transcend merely being an excellent study of its subject, and instead emerge as a worthwhile cultural artefact in its own right. Scholarly yet irreverent, highly serious but always richly entertaining, the book not only sends the reader back to the music it describes, but also repays repeated readings.

The worth, and impact, of Macdonald's work was summarised by UK newspaper The Guardian:

In his book Revolution In The Head, first published in 1994, MacDonald carefully anatomised every record the Beatles made, drawing attention to broad themes, particular examples of inspiration and moments of human frailty alike.

What could have been a dry task instead produced a volume so engagingly readable, so fresh in its perceptions and so enjoyable to argue with that, in an already overcrowded field, it became an immediate hit. Without a hint of sycophancy, MacDonald had managed to describe the magic created by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr in such a way as to reacquaint those who were around at the time with their own original enthusiasm, while alerting listeners of later generations to the precise qualities that had made the Beatles so exceptional. Its introduction alone provides something close to a definitive evocation of the factors that turned the 1960s into 'the sixties'.

Focus

Oddly for a Beatles book, MacDonald focuses on the music, or - as he invariably puts it - the 'records' the group made. Every official Beatles recording is covered, some songs' entries rolling on for a number of pages, some dismissed with just one desultory paragraph. MacDonald achieves a remarkable blend of concision with comprehensiveness, offering up a range of thematic perspectives, from musical theory to socio-cultural analysis, to fleeting biographical vignettes which, by combining penetrating insight with elegantly vivacious language, add up to far more than the sum of their parts.

Structure

Style

MacDonald's style is, in a word, stylish. If you insisted on trying to unpick it, you could say it encompasses elements of academic, musicological, and - pace Frank Zappa - what might best be described as 'classic rock critical' modes. It's actually quite a difficult writing style to satisfactorily describe, but any adequate attempt would surely include such words as 'elegant', 'laconic', 'intelligent', 'direct', and 'precise'. It's simultaneously refined and gritty, often poetic, occasionally flamboyant. MacDonald, basically, writes the way you wish you did, Jack, if only you'd been born with an abundance of talent and then honed your skills for a couple of decades.

Content

Amid a slew of biographies, memoirs, chronologies, and cut-and-paste hack jobs, this book stands out as a lamentably rare study of the Beatles' music. It's a book written by someone who is a Beatles fan but who is also, above all, a critic: MacDonald's passion for the music of the Beatles resonates throughout, but he brings plentiful amounts of objective appraisal to bear upon what he considers to be their lesser achievements. If, when asessing the recorded output of the Beatles, 'lesser achievement' must always be considered a highly qualified term, MacDonald doesn't waste any time dwelling on such relativistic nicities: he routinely states his opinions as though they were incontravertable facts. Which is just as it should be; who wants to read a book full of caveats and imho's? MacDonald has a lot to say about this music, most sensible readers will probably agree with a good deal of it, and in any case half the fun is in having your own preconceptions challenged. The better the critic, the more the reader is likely to find himself equally enjoying agreeing or disagreeing with him.

Some examples? Starting with an easy one, how might the average reader rate 'A Day in the Life'? Great? Just so-so? MacDonald's assessment of the song's importance within the Beatles' canon, and his intriguingly incisive dissection of (some of) its layers of meaning, is preceded by a warning that "more nonesense has been written about this recording than anything else The Beatles produced." MacDonald refutes a number of myths surrounding the song, including the idea that it represents "a sober return to the real world after the drunken fantasy of 'Pepperland'", or "an evocation of a bad trip", or even "a morbid celebration of death".

Rather, this sometimes sombre but always ethereally beautiful work - which Macdonald hails as the Beatles' "finest single achievement" - is, essentially, a "song about perception":

A song not of disillusionment with life itself but of disenchantment with the limits of mundane perception, A DAY IN THE LIFE depicts the 'real' world as an unenlightened construct that reduces, depresses, and ultimately destroys. In the first verse - based, like the last, on a report in the Daily Mail for 17th January 1967 - Lennon refers to the death of Tara Browne, a young millionaire friend of The Beatles and other leading English groups. On 18th December 1966, Browne, an enthusiast of the London counterculture and, like all its members, a user of mind-expanding drugs, drove his light blue Lotus Elan at high speed through red lights in South Kensington, smashing into a parked mini-van and killing himself. Whether or not he was tripping at the time is unknown, though Lennon clearly thought so. Reading te report of the coroner's verdict, he recorded it in the opening verses of A DAY IN THE LIFE, taking the detatched view of the onlookers whose only interest was in the dead man's celebrity. Thus travestied as a spectacle, Browne's tragedy became meaningless - and the weary sadness of the music which Lennon found for his lyric displays a distacne that veers from the dispassionate to the unfeeling.

On the next page in the same newspaper, he found an item whose absurdity perfectly complemented the Tara Browne story: 'There are 4,000 holes in the road in Blackburn, Lancashire, or one twenty-sixth of a hole per peron, according to a council survey.' This - intensified by a surreal reference to the circular Victorian concert venue the Albert Hall (also in South Kensington) - became the last verse. In between, Lennon inserted a verse in which his jaded spectator looks on as the English army wins the war. Prompted by his part in the film How I Won The War three months earlier, this may have been a veiled allusion to Vietnam which, though a real issue to Lennon, would have overheated the song if stated directly.

At one level, A DAY IN THE LIFE concerns the alienating effects of 'the media'. On another, it looks beyond what the Situationists called 'the society of the Spectacle' to the poetic consciousness invoked by the anarchic wall-slogans of May 1968 in Paris (e.g., 'Beneath the pavement, the beach'). Hence the sighing tragedy of the verses is redeemed by the line 'I'd love to turn you on', which becomes the focus of the song. The message is that life is a dream and we have the power, as dreamers, to make it beautiful. In this perspective, the two rising orchestral glissandi may be seen as symbolising simultaneously the moment of awakening from sleep and a spiritual ascent from fragmentation to wholeness, achieved in the resolving E major chord. How the group themselves pictured these passages is unclear, though Lennon seems to have had something cosmic in mind, requesting from Martin, 'a sound like the end of the world' and later describing it as 'a bit of a 2001'. All that is certain is that the final chord was not, as many have since claimed, meant as an ironic gesture of banality or defeat. (It was originally conceived and recorded - Beach Boys style - as a hummed vocal chord.) In early 1967, deflation was the last thing on The Beatles' minds - or anyone else's, with the exception of Frank Zappa or Lou Reed. Though clouded with sorrow and sarcasm, A DAY IN THE LIFE is as much an expression of mystic-psychedelic optimism as the rest of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The fact that it achieves its transcendent goal via a potentially dissillusioning confrontation with the 'real' world is precisely what meakes it so moving.

Few in number are the Beatles fans who wouldn't rank that song highly. Even so, lodging the straight-faced claim that it's "their finest single achievement", is still a bold statement. And using unqualified terms such as 'the message is...' always runs the risk of seeming arrogant, didactic, or just plain wrong. It's a testament to the strength of MacDonald's work that such robust opinions never stick in the reader's throat. It should be made clear, also, that the above passage is just a few paragraphs excerpted from several pages on 'A Day in the Life'. The entry for that song alone is so rich and varied, so liberally studded with telling details and points for potential discussion, that it probably contains more wisdom and contention than the average critic could pack into an entire book. It's not so much food for thought as an intellectual banquet, to be returned to and picked over for weeks, if not years, to come.

On the other hand, consider MacDonald's opinion on 'Across the Universe':

After the agressive sarcasm of I AM THE WALRUS, it is sad to find Lennon, some months and several hundred acid trips later, chanting this plaintively babyish incantation. [...] Lennon was impressed with this lyric, trying on several later occasions to write in the same metre. Sadly, its amorphous pretensions and listless melody are rather too obviously the products of acid grandiosity rendered gentle by sheer exhaustion. [...] While a Beatle, Lennon was rarely boring. He made an unwanted exception with this track.

It's a characteristically trenchant dismissal of a song many readers might wish to defend. But, crucially, even the most indulgent tolerator of the Let It Be album's many over-eggings, will at least grant MacDonald a fair hearing. It's a sign of how persuasive a critic he is that the impulse is not to scoff at his harsh assessment, but to feel impelled to at least think twice before moving on.

MacDonald's song-by-song analysis of the Beatles' records takes up the bulk of the book. But it is preceded by an introductory essay, 'Fabled Foursome, Disappearing Decade', which sets the Beatles in historical and cultural context, and represents an attempt at resolving a central paradox arising from the group's relationship to the decade they did so much to define: with the passing of time, The Beatles' reputation has only become more and more enshrined and unimpeachable, yet the decade which they were so much a part of, has become reviled, despised and so misunderstood that it has effectively become 'lost'.

At the time, MacDonald says, "the spirit of that era disseminated itself across generations, suffusing the Western world with a sense of rejuvenating freedom comparable to the joy of being let out of school early on a sunny afternoon." But the decade has since become a key battleground for what are sometimes known as the 'Culture Wars', right-wing politicians and commentators tending to blame all of modern society's ills on the 'permissive' 1960s. Conversely, many on the Left have long sought exmplanations for how (and why) the various 'revolutions' and 'movements' of the Sixties failed, and these questions have fuelled some of the most insightful political fiction written about the era, notably Thomas Pynchon's 1990 novel 'Vineland', which shares many of MacDonald's themes.

It's obvious that MacDonald has very little sympathy for the Right's reductive and revisionist view of the Sixties, but readers looking for a robust defence of the idealistic impulses of the hippies and radicals whose sensibilities came to be seen as broadly representative of the generational spirit of the times, may also be disappointed. He certainly has plenty of positive things to say about them, especially when considered next to later social groups who looked on them with agressive disdain:

The hippie outlook, if so hererogeneous a group can be said to have cleaved to one position, was by no measn flippant. Theirs was a kaleidoscopically inventive culture, actively devoted to the acquisition of self-knowledge and the promotion of fundamental social change. In rejecting the hippies, the punks of 1976-7 discarded only a caricature, coming nowhere near an adequate grasp of what they imagined they were rebelling against.

As with his assessments of the Beatles' records, he doesn't hesitate to decry the more negative aspects of the young radicals of the era, noting that "the late Sixties' youth rebellion declined into an ugly farce of right-on rhetoric and aimless violence". But he also reminds us that "it would be a gross distortion to pretend that this was not substantially provoked by the stone-faced repressive arrogance of the establishment in those days."

MacDonald's thesis is a complex one, and can't be easily summarised. At its heart is his assertion that the "real movers and shakers" of the Sixties were not the student demonstrators, flower children, and 'beautiful people', but the greater mass of "ordinary people". The "true revolution" of the 1960s was "an inner one of feeling and assumption: a revolution in the head." The Sixties were, MacDonald points out, a transitional phase, rife with paradoxes and contradictions, not least that the social trends which seemed to sustain the more radical elements, were the very same forces which led to a fragmentation of consensus and rise of materilistic indiviualism, paving the way for "Margaret Thatcher's deregulated anti-society" in the 1980s.

The truth is that the Sixties inaugurated a post-religious age in which neither Jesus nor Marx is of interest to a society now functionong mostly below the level of the rational mind in an emotional/physical dimension of personal appetite and private insecurity."

A more bitter irony is that the Punks of the late 70s, and indeed the Thatcherites and Reaganites who dominated the zeitgest of the 1980s, had a lot more in common with the real spirit of the decade they so despised than they could ever bring themselves to realise:

The irony of modern right-wing antipathy to the Sixties is that this much-misunderstood decade was, in all but the most superficial senses, the creation of the very people who voted for Thatcher and Reagan in the Eighties. It is, to put it mildly, curious to hear Thatcherites condemn a decade in which ordinary folk for the first time aspired to individual self-determination and a life of material security within an economy of high employment and low inflation. The social fragmentation of the Nineties which rightly alarms conservatives was created neither by the hippies (who wanted us to 'be together') nor by the New Left radicals (all of whom were socialists of some description).

So far as anything in the Sixties can be blamed for the demise of the compound entity of society it was the natural desire of the 'masses' to lead easier, pleasanter lives, own their own homes, follow their own fancies and, as far as possible, move out of the communal collective completely. The truth is that, once the obsolete Christian compact of the Fifties had broken down, there was nothing - apart from, in the last resort, money - holding Western civilisation together. Indeed, the very labour-saving domestic appliances launched onto the market by the Sixties' consumer boom speeded the melt-down of communality by allowing people to function in a private world, segregated from each other by TVs, telephones, hi-fi systems, washing-machines and home cookers. (The popularity in the Eighties of the answering machine - the phone-call you don't have to reply to - is another sign of ongoing desocialisation by gadgetry.)

It's a persuasive view, though perhaps not one to win MacDonald any friends on either side of the ideological divide. One of the subtlest strands of his argument concerns the relationship between the way social and cultural changes were accellerated, and even brought about by, modern technologies of convenience, and the impact of musical and recording technology on the art of popular music, all of which are depicted as part of a steady cultural decline:

"A malignant rot has spread through the Western mind since the mid-Seventies: the virus of meaninglessness. Yet this infection threatens all ideologies, Left or Right, being at root no more than a levelling crusade on behalf of the aesthetically deprived - a Bad Taste Liberation Front. The reason why cultural relativism has caught on is not because ordinary people read Derrida but because the trickle-down essence of Deconstruction suits both the trash aesthetic of media-hounds and the philistinism of Essex Man.

The destabilising social and psychological evolution witnessed since the Sixties stems chiefly from the success of affluence and technology in realising the desires of ordinary people. The countercultural elements usually blamed for this were in fact resisting an endemic process of disintegration with its roots in scientific materialism. Far from adding to this fragmentation, they aimed to replace it with a new social order based on either love-and-peace or a vague anarchistic European version of revolutionary Maoism. When contemporary right-wing pundits attack the Sixties, the identify a momentous overall development but ascribe it to the very forces which most strongly reacted against it. The counterculture was less an agent of chaos than a marginal commentary, a passing attempt to propose alternatives to a waning civilisation.

Ironically, the harshest critics of the Sixties are its most direct beneficiaries: the political voices of materialistic individualism. Their recent contribution to the accelerated social breakdown inaugurated around 1963 - economic Darwinism wrapped in self-contradictory socio-cultural prejudices - hasn't helped matters, yet even the New Right can't be held responsible for the multifocal and fragmented techno-decadence into which the First World is currently sinking as if into a babbling, twinkling, microelectronically pulsing quicksand. In the Nineties, the fashion is to reprove others for our own faults; yet even if we take the blame for ignoring our limitations and eroding our own norms over the last thirty years, it is hard to imagine much, short of fascism or a Second Coming, that will put Humpty back together again.

It's not a cheerful outlook, but it would be hard to argue that it is not based on certain irrefutable truths.

That the twin phenomena of 'The Beatles' and 'The Sixties' were integral to one another is a theme which runs right through MacDonald's book. With subtle forcefulness, he uses the records the group made to illustrate how in tune with their times they were, and how they also played a role which was broadly similar to that played in America by Bob Dylan, in that they had a significant hand in shaping those times (although they had a much more globally pervasive effect). The Beatles changed the world; sometimes - indeed, maybe even mostly - when they weren't even trying to:

Indeed, the American folk-protest movement had thrust plain speaking so obtrusively into the pop domain that every transient youth idol was then routinely interrogated concerning his or her 'message' to humanity. If it has any message at all, that of I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND is 'Let go - feel how good it is'. This though (as conservative commentators knew very well) implied a fundamental break with the Christian bourgeois status quo. Harbouring no conscious subversive intent, The Beatles, with this potent record, perpetrated a culturally revolutionary act. As the decade wore on and they began to realise the position they were in, they began to do the same thing more deliberately.

It would be a mistake, though, to portray this as a 'political' book, or even one whose central concern was pop-cultural theorising. The vast majority of the text is made up of concise yet wide-ranging descriptions of the Beatles' music. The reader is compelled to come back and re-read any number of entries, not just to soak up more of the facts and insights, but to enjoy the elegance of the writing, to nod in heartfelt agreement (and, now and then, to reluctantly dissent), or just to indulge in the reveries this truly great book inspires.

It's a book that has to be read, and its many pleasures cannot be adequately summed up. A fairly representative sample might be this, the final paragraph in MacDonald's description of 'Happiness is a Warm Gun':

In the end, the most purely Lennonian aspect of HAPPINESS IS A WARM GUN is its extreme ambiguity. From an initial mood of depression, it ascends through irony, self-destructive despair, and obscurely renewed energy to a finale that wrests exhausted fulfilment from anguish. Grippingly uneasy listening, the track's tense blend of sarcasm and sincerity stays unresolved until its final detumescent downbeat.

Elsewhere, in the entry for 'Help!', what MacDonald has to say about the finishing touches made to the song by The Beatles could, without too much adjustment, be taken as a pretty accurate metaphor for what MacDonald himself does:

To finish, Starr overdubbed tambourine, and Harrison taped his guitar part, descending at the end of each chorus on a cross-rythm arpeggio run in the style of Nashville guitarist Chet Atkins. (This, and Starr's straight-quaver fills against the song's fast shuffle beat, are good examples of the group's care in painting characterful touches into every corner of their best work.)

Every corner of this book is filled with characterful touches. You can look, but you will not find this level of writing in any other Beatles book.