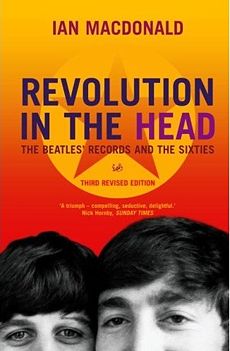

Revolution in the Head

From Beatles Wiki - Interviews, Music, Beatles Quotes

Synopsis

This book hit the mid-1990s pop-cultural scene like a bolt from the blue. Well over a quarter of a century since they was Fab, it might have seemed that everything worth saying about the Beatles had already been said, several times. At that stage, the suggestion that someone could produce a genuinely fresh perspective on this most catergorised, analysed, and anthologised of pop groups seemed only marginally less unlikely than the idea that a new band might emerge from the pop field whose music could hold a candle to the imperviously incomparable legacy of the world's best-loved Liverpudlians.

But MacDonald's words leap off the page with a freshness and sense of excitment reminiscent of, say, the opening seconds of 'I Want to Hold Your Hand'. A chronological song-by-song analysis of the Beatles' output, 'Revolution in the Head' manages to make that rarest of leaps: to transcend merely being an excellent study of its subject, and instead emerge as a worthwhile cultural artefact in its own right. Scholarly yet irreverent, highly serious but always richly entertaining, the book not only sends the reader back to the music it describes, but also repays repeated readings.

The worth, and impact, of Macdonald's work was summarised by UK newspaper The Guardian:

In his book Revolution In The Head, first published in 1994, MacDonald carefully anatomised every record the Beatles made, drawing attention to broad themes, particular examples of inspiration and moments of human frailty alike.

What could have been a dry task instead produced a volume so engagingly readable, so fresh in its perceptions and so enjoyable to argue with that, in an already overcrowded field, it became an immediate hit. Without a hint of sycophancy, MacDonald had managed to describe the magic created by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr in such a way as to reacquaint those who were around at the time with their own original enthusiasm, while alerting listeners of later generations to the precise qualities that had made the Beatles so exceptional. Its introduction alone provides something close to a definitive evocation of the factors that turned the 1960s into 'the sixties'.

Focus

Oddly for a Beatles book, MacDonald focuses on the music, or - as he invariably puts it - the 'records' the group made. Every official Beatles recording is covered, some songs' entries rolling on for a number of pages, some dismissed with just one desultory paragraph. MacDonald achieves a remarkable blend of concision with comprehensiveness, offering up a range of thematic perspectives, from musical theory to socio-cultural analysis, to fleeting biographical vignettes which, by combining penetrating insight with elegantly vivacious language, add up to far more than the sum of their parts.

Structure

Style

Content

Amid a slew of biographies, memoirs, chronologies, and cut-and-paste hack jobs, this book stands out as a lamentably rare study of the Beatles' music. It's a book written by someone who is a Beatles fan but who is also, above all, a critic: MacDonald's passion for the music of the Beatles resonates throughout, but he brings plentiful amounts of objective appraisal to bear upon what he considers to be their lesser achievements. If, when asessing the recorded output of the Beatles, 'lesser achievement' must always be considered a highly qualified term, MacDonald doesn't waste any time dwelling on such relativistic nicities: he routinely states his opinions as though they were incontravertable facts. Which is just as it should be; who wants to read a book full of caveats and imho's? MacDonald has a lot to say about this music, most sensible readers will probably agree with a good deal of it, and in any case half the fun is in having your own preconceptions challenged. The better the critic, the more the reader is likely to find himself equally enjoying agreeing or disagreeing with him.

Some examples? Starting with an easy one, how might the average reader rate 'A Day in the Life'? Great? Just so-so? MacDonald's assessment of the song's importance within the Beatles' canon, and his intriguingly incisive dissection of (some of) its layers of meaning, is preceded by a warning that "more nonesense has been written about this recording than anything else The Beatles produced." MacDonald refutes a number of myths surrounding the song, including the idea that it represents "a sober return to the real world after the drunken fantasy of 'Pepperland'", or "an evocation of a bad trip", or even "a morbid celebration of death".

Rather, this sometimes sombre but always ethereally beautiful work - which Macdonald hails as the Beatles' "finest single achievement" - is, essentially, a "song about perception":

A song not of disillusionment with life itself but of disenchantment with the limits of mundane perception, A DAY IN THE LIFE depicts the 'real' world as an unenlightened construct that reduces, depresses, and ultimately destroys. In the first verse - based, like the last, on a report in the Daily Mail for 17th January 1967 - Lennon refers to the death of Tara Browne, a young millionaire friend of The Beatles and other leading English groups. On 18th December 1966, Browne, an enthusiast of the London counterculture and, like all its members, a user of mind-expanding drugs, drove his light blue Lotus Elan at high speed through red lights in South Kensington, smashing into a parked mini-van and killing himself. Whether or not he was tripping at the time is unknown, though Lennon clearly thought so. Reading te report of the coroner's verdict, he recorded it in the opening verses of A DAY IN THE LIFE, taking the detatched view of the onlookers whose only interest was in the dead man's celebrity. Thus travestied as a spectacle, Browne's tragedy became meaningless - and the weary sadness of the music which Lennon found for his lyric displays a distacne that veers from the dispassionate to the unfeeling.

On the next page in the same newspaper, he found an item whose absurdity perfectly complemented the Tara Browne story: 'There are 4,000 holes in the road in Blackburn, Lancashire, or one twenty-sixth of a hole per peron, according to a council survey.' This - intensified by a surreal reference to the circular Victorian concert venue the Albert Hall (also in South Kensington) - became the last verse. In between, Lennon inserted a verse in which his jaded spectator looks on as the English army wins the war. Prompted by his part in the film How I Won The War three months earlier, this may have been a veiled allusion to Vietnam which, though a real issue to Lennon, would have overheated the song if stated directly.

At one level, A DAY IN THE LIFE concerns the alienating effects of 'the media'. On another, it looks beyond what the Situationists called 'the society of the Spectacle' to the poetic consciousness invoked by the anarchic wall-slogans of May 1968 in Paris (e.g., 'Beneath the pavement, the beach'). Hence the sighing tragedy of the verses is redeemed by the line 'I'd love to turn you on', which becomes the focus of the song. The message is that life is a dream and we have the power, as dreamers, to make it beautiful. In this perspective, the two rising orchestral glissandi may be seen as symbolising simultaneously the moment of awakening from sleep and a spiritual ascent from fragmentation to wholeness, achieved in the resolving E major chord. How the group themselves pictured these passages is unclear, though Lennon seems to have had something cosmic in mind, requesting from Martin, 'a sound like the end of the world' and later describing it as 'a bit of a 2001'. All that is certain is that the final chord was not, as many have since claimed, meant as an ironic gesture of banality or defeat. (It was originally conceived and recorded - Beach Boys style - as a hummed vocal chord.) In early 1967, deflation was the last thing on The Beatles' minds - or anyone else's, with the exception of Frank Zappa or Lou Reed. Though clouded with sorrow and sarcasm, A DAY IN THE LIFE is as much an expression of mystic-psychedelic optimism as the rest of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The fact that it achieves its transcendent goal via a potentially dissillusioning confrontation with the 'real' world is precisely what meakes it so moving.

Few in number are the Beatles fans who wouldn't rank that song highly. Even so, lodging the straight-faced claim that it's "their finest single achievement", is still a bold statement. And using unqualified terms such as 'the message is...' always runs the risk of seeming arrogant, didactic, or just plain wrong. It's a testament to the strength of MacDonald's work that such robust opinions never stick in the reader's throat. It should be made clear, also, that the above passage is just a few paragraphs excerpted from several pages on 'A Day in the Life'. The entry for that song alone is so rich and varied, so liberally studded with telling details and points for potential discussion, that it probably contains more wisdom and contention than the average critic could pack into an entire book. It's not so much food for thought as an intellectual banquet, to be returned to and picked over for weeks, if not years, to come.

Criticism

Editions

References